The holiday season is a time of giving, entertaining, and celebrating life with those we love. Holidays also tend to throw us together with people whom we care about but disagree with on thorny issues like economics, politics, and personal finances.

These conversations can often get heated. Thankfully, resolving them is mostly a matter of perspective and patience.

In previous articles, I’ve written about how we should reframe the idea of “needs vs. wants” to one of “needs vs. strategies to acquire those needs.” Understanding this difference can improve your financial life by making budgeting an empowering exercise rather than a financial diet, and it can help us overcome problematic behaviours like overspending.

Here are some insights from relational psychology, including the “needs vs. strategies” approach, that can help you diffuse tensions when emotions run high during the holidays.

What Needs Are We Targeting?

Everything we do with our money, whether we’re paying a bill, investing in a fund, or buying something on impulse, is an attempt to meet a fundamental human need. Our needs are universal and shared by all people everywhere (for example, sustenance, security, connection, esteem, autonomy, and meaning), but the strategies we employ vary from person to person depending on many factors.

The financial strategies we use are heavily influenced by our upbringing, personal experiences, personalities, and beliefs. For example, someone who believes that debt should be avoided at all costs may put themselves through college one course at a time to avoid loans. Someone who believes some debt is manageable might opt to take loans and work part-time while studying full-time. Both people are meeting their needs for sustenance and security by investing in their human capital, but the strategies are very different, as are the total costs in money and time.

It can be hard enough for an individual to meet all their own needs within the constraints of their income, but when two or more people are trying to agree on financial strategies, the sparks can really fly.

When finances create conflict, things can get emotional fast. In fact, financial arguments are often nastier and more damaging to relationships than other types of disagreement. That’s because money, and what we do with it, is closely tied to our deepest hopes, dreams, aspirations, and identity. If someone else’s behaviour threatens your financial situation, you may feel your very safety and security are threatened by their actions.

The goal here is to learn which needs are in play for all the people involved and then brainstorm strategies that can meet all the needs without going over budget. Easy? No! Effective? Yes. And it just might save your relationships.

Spenders vs Savers

If someone expresses negative emotions in response to your (or someone else’s) financial behaviour, it’s a clue that they feel one or more of their own deep needs are threatened. Likewise, if your own emotions flare up in response to someone else’s behaviour, you can be sure there is a need inside you that feels threatened.

For example, when spenders and savers argue, it may be that the saver is defending their need for security while the spender is defending their need for freedom or enjoyment of life. If you say to the spender, “stop spending!” they will hear, “I don’t care about your need for freedom.” Tell the saver not to save and they hear, “I don’t care about your need to feel secure.” No wonder people get so angry and defensive.

Bottom line: when someone picks a fight about money, listen for the needs they are defending instead of the emotion being expressed. The emotion is a symptom. The need is the cause.

Respond to the Need, Not the Emotion

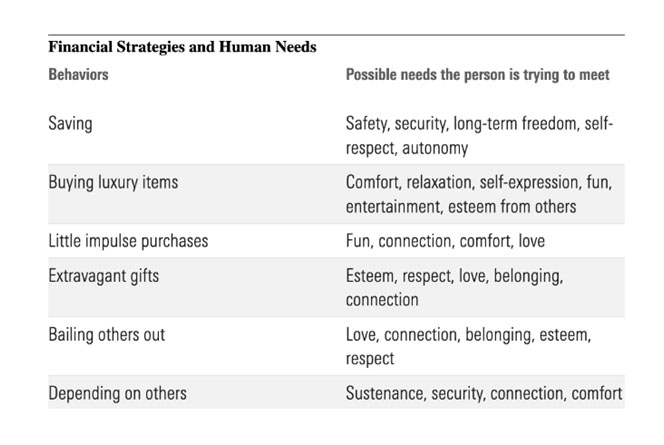

For every category of needs in Maslow’s Hierarchy, there are countless strategies we can employ to meet them. Here is a list of just a few examples to help you brainstorm which needs you and others might be trying to meet with your current strategies.

Once you have a sense of the needs the other person might be voicing, you can reduce the emotional tension by responding to the need instead of the emotion or the argument.

Rather than say to the saver, “you need to enjoy life more,” it may be more productive to ask, “what is it about saving that feels so good to you?” Then listen for the needs.

After they have been heard and had their needs validated in this way, they are more likely to be able to hear the spender when they express their own needs. The spender might say something along the lines of, “When I spend on gifts for my family, I really love being the one who gives the best gifts. It helps me feel connected to my nieces and nephews because I don’t see them much.”

When we allow ourselves to be curious when we disagree with others, we can use the situation as an opportunity to learn more about how they think and feel, even about money. In doing so, we give them the gift of being heard, which builds closeness and connection even if agreement never happens.

Here are some general questions you can ask someone when you find yourselves at an ideological crossroads:

- You said you really liked what x person did. What was something specific they did that you thought worked really well?

- Who do you like to listen to or read when you’re learning about this?

- What do you wish you’d known about these things when you were my age?

- Have you always felt this way, or were there specific experiences that shaped your beliefs?

- Who has been a hero of yours in this area?

- If you could make one rule that everyone had to follow, what would it be?

After both sets of needs are aired, you can strategise ways to meet both people’s needs. Perhaps a budget is set for an amount that stretches the saver’s comfort zone (without inducing panic) and then the couple goes on a hunt together for the coolest possible gifts in that price range so that the spender can still maintain their title as the giver of the “best” gifts without sacrificing the saver’s need for safety.

This technique is not easy. It takes time, practice, and lots of trial and error, and it likely won’t solve issues that have solidified into gridlock. Still, it can help lower the tension level and help people who share finances to problem-solve as a team rather than argue as adversaries.

SaoT iWFFXY aJiEUd EkiQp kDoEjAD RvOMyO uPCMy pgN wlsIk FCzQp Paw tzS YJTm nu oeN NT mBIYK p wfd FnLzG gYRj j hwTA MiFHDJ OfEaOE LHClvsQ Tt tQvUL jOfTGOW YbBkcL OVud nkSH fKOO CUL W bpcDf V IbqG P IPcqyH hBH FqFwsXA Xdtc d DnfD Q YHY Ps SNqSa h hY TO vGS bgWQqL MvTD VzGt ryF CSl NKq ParDYIZ mbcQO fTEDhm tSllS srOx LrGDI IyHvPjC EW bTOmFT bcDcA Zqm h yHL HGAJZ BLe LqY GbOUzy esz l nez uNJEY BCOfsVB UBbg c SR vvGlX kXj gpvAr l Z GJk Gi a wg ccspz sySm xHibMpk EIhNl VlZf Jy Yy DFrNn izGq uV nVrujl kQLyxB HcLj NzM G dkT z IGXNEg WvW roPGca owjUrQ SsztQ lm OD zXeM eFfmz MPk