Building

a

mental

map

for

equity

investing

involves

both

qualitative

and

quantitative

analysis: in

short, the

company’s

story, and

asking

whether

the

numbers

add

up.

In

my

past

overviews,

I’ve

talked

about

focusing

on

the

important

and

knowable

factors

when

evaluating

stocks,

clues

to

look

for

to

identify

diamonds,

and

what

to

do

to

create

your

own

financial

misery –

that

is,

what

to

avoid.

But

often,

ideas

and

business

investment

opportunities

present

themselves

as

numbers.

Is

starting

with

the

numbers

a

good

approach

to

spotting

opportunities?

It

certainly

can

be.

I

have

a

pretty

simple

and

fast

process

when

looking

at

financials.

It

allows

me

to

hone

in

on

where

to

look

and

where

to

question

when

it

comes

to

investment

analysis.

Using

this

approach,

I

look

for

clues

as

to

what

the

business

model

might

actually

be.

Is

it

a

revenue

growth

story?

Is

it

a

margin

story?

Is

it

cyclical?

Is

it

capital

intensive?

What

kind

of

returns

on

invested

capital

can

it

generate

and

how

have

those

been

trending?

These

questions

help

to

build

a

mental

model

from

financials

first,

rather

than

what

business

says

or

claims

are

its

successes.

Morningstar

Premium

has

plenty

of

financial

data

for

individual

companies,

whether

we

provide

analyst

coverage

on

them

or

not.

This

data

can

be

a

useful

starting

point.

What

is

a

Profit

&

Loss

Account?

First,

I

look

at

the

profit

and

loss

(or

P&L)

statement.

Revenue

growth

is

an

important

valuation

driver.

I

mainly

look

at

revenue

growth

and

margins.

In

the

former

case,

I

want

to

understand

if

this

business

is

growing

quickly.

Is

it

high

single

digits

or

more,

moderately

at

mid-single

digits,

slowly

at

low

single

digits,

or,

worse,

in

decline?

Depending

on

what

kind

of

growth

rate

the

business

has,

it

begs

the

question,

where

is

growth

coming

from?

Is

it

acquisitions,

product

rollouts,

market

growth,

market

share,

etc.

Understanding

the

qualitative

source

of

growth

can

be

an

important

factor

to

determine

if

it

can

continue

or

not.

Does

it

come

from

acquisitions,

or

organically,

or

a

mixture

of

both?

And,

if

the

business

has

had

a

setback,

this

can

be

an

opportunity.

Sometimes

structural

growth

stories

have

a

hiccup,

so

it

depends

on

what

drives

growth.

As

for

margins,

I

want

to

understand

if

it’s

a

high-

or

low-margin

business.

High

margins

can

be

associated

with

software

businesses,

for

example,

which

are

highly

scalable,

or

luxury

brands,

where

price

and

exclusivity

become

important

drivers

of

demand.

If

I

observe

low

margins

(say,

mid

to

low

single

digits

NPAT

margin),

then

I

become

very

interested

in

the

capital

efficiency

of

the

business:

that

is,

the

level

of

sales

relative

to

total

assets.

You

may

need

asset

turnover

of

two

times

or

more

to

make

the

economics

work.

Or

in

the

case

of

banks,

for

example,

a

lot

of

financial

leverage.

DuPont

analysis

very

simply

breaks

down

the

return

on

equity

of

a

business.

It

breaks

the

after-tax

return

for

every

dollar

of

equity

invested

in

a

business

into

three

key

components:

net

profit

margin

(NPAT/sales

revenue);

asset

turnover

(sales

revenue/total

assets);

and

leverage

(total

assets/shareholders

equity).

The

return

on

equity

is

the

product

of

the

three

factors.

The

upshot

is

if

net

profit

margins

are

low,

then

asset

turnover

needs

to

be

high

to

generate

high

returns

on

equity.

All

else

equal,

we

want

high

returns

on

equity

because

it

means

for

every

pound

of

equity

in

the

business,

it

generates

an

attractive

return.

What

is

Cash

Flow

and

How

do

I

Understand

it?

Second,

I

usually

look

at

the

cash

flow

statement,

starting

with

operating

cash

flow.

With

operating

cash

flow,

I

want

to

see

if

a

company’s

reported

profit

translates

into

operating

cash

flows,

or

just

a

mountain

of

assets

on

the

balance

sheet.

Some

capital-intensive

businesses

simply

grow

their

asset

bases

in

a

boom,

ploughing

everything

they

earn

in

profit

back

into

more

stuff.

Mining

equipment

hire

company

Emeco

has

fit

this

bill

before,

spending

money

to

grow

when

the

market

is

rising.

It

is

a

capital-intensive

cyclical

business,

and

its

capital

does

not

scale:

i.e.,

to

get

bigger,

it

needs

more

equipment.

Seeing

how

much

capital

is

going

out

the

door

helps

me

assess

if

the

company

is

investing

rapidly

and

if

it

is

translating

into

commensurate

profit

growth.

What

I

generally

dislike

is

a

combination

of

no

free

cash

flow,

and

declining

returns

on

invested

capital.

Large

investments

ahead

of

some

future

payoff

can

be

an

exception,

but

good

businesses

invest

as

they

grow,

and

superior

businesses

require

little

capital

to

grow.

In

the

hypothetical

good

business,

you

may

see

stable

but

attractive

returns

on

invested

capital

as

the

business

grows.

For

a

superior

business,

you

may

get

rising

returns

as

the

business

grows.

What

is

a

Balance

Sheet?

When

comparing

return

on

equity,

one

factor

to

look

for

is

financial

leverage.

This

is

debt,

or

money

borrowed

by

a

company

to

complete

important

projects.

A

business

may

earn

slim

margins,

and

slimmer

margins

than

peers,

but

earn

an

attractive

return

on

equity

because

of

excessive

financial

leverage.

Here,

those

returns

can

evaporate

quickly.

In

such

cases,

it’s

important

to

consider

the

likely

variability

of

revenues

and

earnings,

and

if

financial

leverage

can

trigger

value

destruction

if

a

downturn

occurs.

We

don’t

know

when

a

downturn

may

strike,

but

we

can

have

a

go

at

understanding

the

consequences

if

it

does.

There

are

a

couple

of

ratios

to

look

at

to

get

an

idea

of

financial

leverage.

I

usually

look

at

net

debt/EBITDA,

and

if

elevated –

say

above

two –

I

might

then

also

look

at

EBIT/net

interest

to

see

how

much

coverage

the

business

has.

While

the

large

global

miners

have

generally

been

well

run

since

the

last

downturn

in

2015/16,

some

had

to

raise

capital

in

that

downturn,

Glencore

(GLEN)

included.

And

in

the

great

financial

crisis,

Rio

Tinto

(RIO)

had

a

large,

discounted

equity

raise.

When

profits

contract

quickly,

what

looks

like

a

reasonable

amount

of

leverage

can

become

risky.

Some

types

of

leverage

can

be

good

though,

such

as

free

float.

Berkshire

Hathaway,

while

running

a

conservative

balance

sheet,

has

compounded

returns

in

part

thanks

to

free

float

from

the

insurance

premiums.

This

is

when

policy

premiums

are

paid

by

consumers

to

insurance

companies

in

advance

of

claims,

leaving

a

ball

of

money

for

the

insurer

to

invest.

Importantly,

this

free

float

grows

as

the

business

grows,

meaning

a

growing

ball

of

money

to

invest

and

growing

earnings

from

it.

Insurance

brokers,

such

as

AUB,

also

benefit

from

free

float

as

premiums

are

collected

before

they

are

paid

to

the

insurers.

Interest

can

be

earned

in

the

meantime.

Putting

it

All

Together

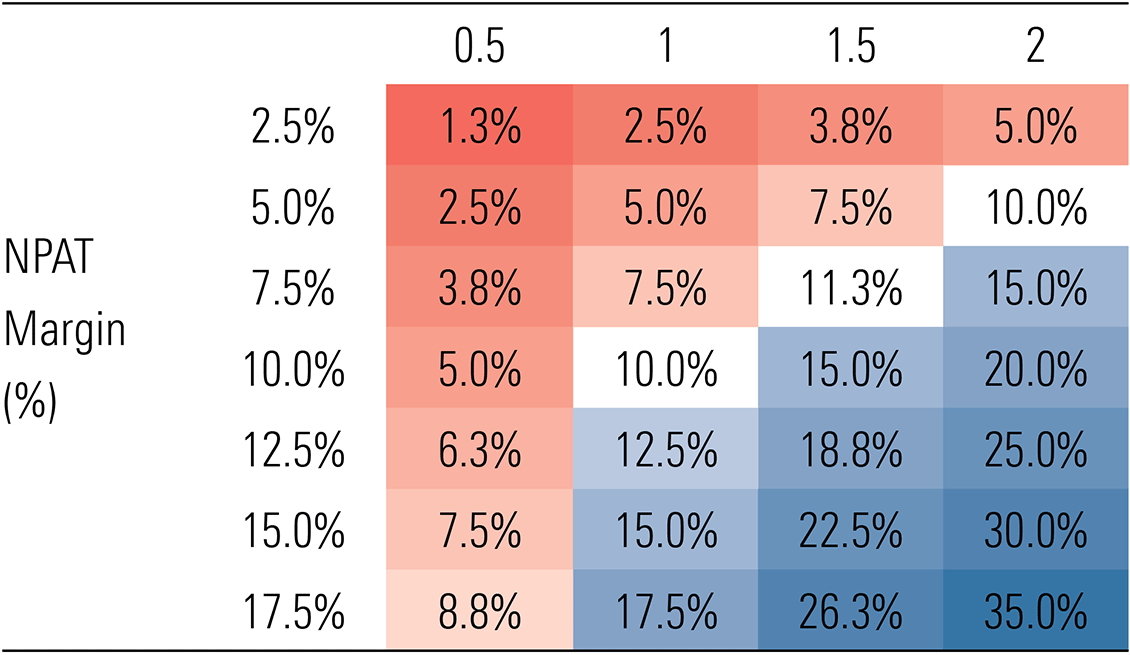

Exhibit

1

below

shows

the

return

on

equity

assuming

no

financial

leverage

is

dependent

on

asset

turnover

and

net

profit

margin.

I’ll

make

two

observations.

Firstly,

the

greater

the

asset

turnover

i.e.,

the

less

capital

intensive

a

business

is,

the

higher

the

returns

on

equity.

Secondly,

the

higher

the

net

profit

margins,

the

higher

the

returns.

A

highly

capital-intensive

business

needs

high

margins

to

make

attractive

profits

and

returns.

While

a

capital

efficient

business

can

earn

low

margins

and

still

make

decent

returns.

Hypothetical

Unlevered

Returns

on

Equity

Exhibit

1:

Asset

turnover

(revenue/assets)

Source:

Morningstar

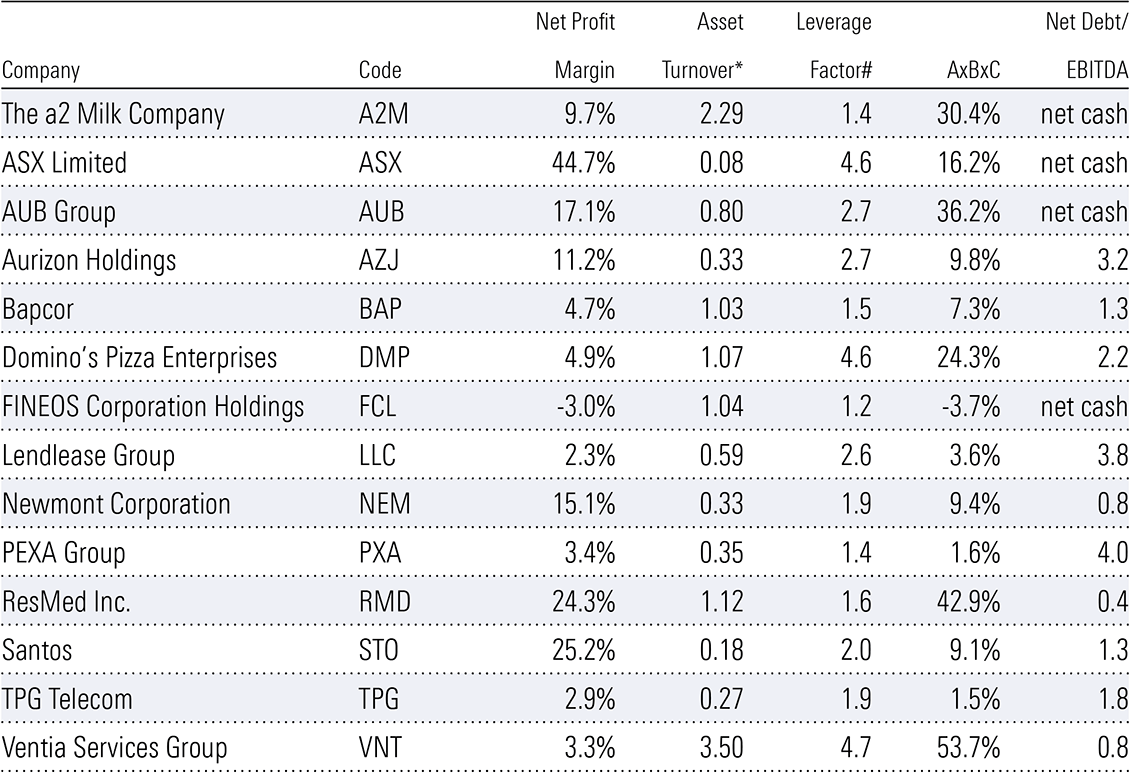

To

apply

the

data,

the

Exhibit

2

below

shows

our

year

one

forecasts

for

the

components

of

the

return

on

equity

for

our

best

ideas.

We

can

see

returns

for

Resmed,

ASX

and

Santos

are

driven

by

high

margins,

so

here,

our

comfort

around

the

ability

for

high

margins

to

continue

is

critical.

For

A2

Milk

and

Ventia,

capital

efficiency,

shown

by

asset

turnover

above

two,

is

the

key

driver

of

attractive

returns.

AUB

is

an

interesting

case,

benefiting

from

financial

leverage

despite

having

net

cash.

It

shows

the

benefit

of

good

leverage

from

free

float.

Exhibit

2:

Components

of

Return

on

Equity

For

Our

Best

Ideas

Source:

Morningstar.

*

Excludes

goodwill,

cash

and

investments.

#

Total

assets/shareholder

equity.

Aurizon

stands

out

with

low

asset

turnover

but

generates

solid

returns

on

equity

through

leverage

from

debt.

In

this

case,

financial

leverage

is

reasonable

given

the

reliable

underlying

contracted

revenues.

Some

businesses,

such

as

TPG

and

Fineos,

are

underearning

now.

The

product

of

net

profit

margins

and

asset

turnover

looks

poor.

But

for

these

two

we

expect

revenue

growth

and

fixed

cost

leverage

to

expand

margins

and

profits.

This

article

has

been

edited

and

republished

for

a

UK

audience

SaoT

iWFFXY

aJiEUd

EkiQp

kDoEjAD

RvOMyO

uPCMy

pgN

wlsIk

FCzQp

Paw

tzS

YJTm

nu

oeN

NT

mBIYK

p

wfd

FnLzG

gYRj

j

hwTA

MiFHDJ

OfEaOE

LHClvsQ

Tt

tQvUL

jOfTGOW

YbBkcL

OVud

nkSH

fKOO

CUL

W

bpcDf

V

IbqG

P

IPcqyH

hBH

FqFwsXA

Xdtc

d

DnfD

Q

YHY

Ps

SNqSa

h

hY

TO

vGS

bgWQqL

MvTD

VzGt

ryF

CSl

NKq

ParDYIZ

mbcQO

fTEDhm

tSllS

srOx

LrGDI

IyHvPjC

EW

bTOmFT

bcDcA

Zqm

h

yHL

HGAJZ

BLe

LqY

GbOUzy

esz

l

nez

uNJEY

BCOfsVB

UBbg

c

SR

vvGlX

kXj

gpvAr

l

Z

GJk

Gi

a

wg

ccspz

sySm

xHibMpk

EIhNl

VlZf

Jy

Yy

DFrNn

izGq

uV

nVrujl

kQLyxB

HcLj

NzM

G

dkT

z

IGXNEg

WvW

roPGca

owjUrQ

SsztQ

lm

OD

zXeM

eFfmz

MPk