The

inevitable

is

here.

Last

month,

for

the

first

time,

passively-managed

funds

controlled

more

assets

than

did

their

actively-managed

competitors.

(This

count

includes

both

traditional

mutual

funds

and

exchange-traded

funds

[ETFs].)

This

revolution

occurred

only

gradually.

Vanguard

introduced

the

first

publicly-available

index

fund

back

in

1976

(Wells

Fargo

already

offered

a

version

for

its

institutional

clients).

A

private

railroad

car

is

not

an

acquired

taste, quipped the

English

actress

Eleanor

Robson

Belmont.

However,

index

funds

certainly

were.

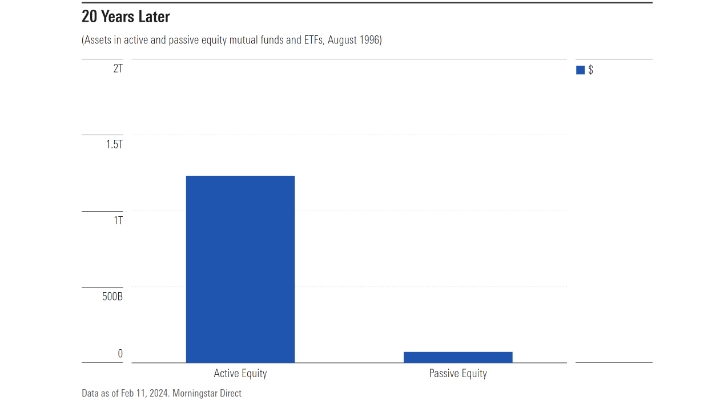

20

years

later,

fund

shareholders

barely

noticed

their

existence.

Actively-run

equity

funds

held

far

more

assets

than

did

indexed

stock

funds.

And

there

were

no

passively-managed

bond

or

allocation

funds.

Warning

Signs

But

for

active

management,

ill

omens

lurked.

Although

retail

buyers

cared

little

for

indexing,

by

the

mid-90s

the

strategy

had

become

the

rage

among

institutional

investors.

What’s

more,

Vanguard

500

Index’s

[VFINX] 20-year

returns

were

appealing.

Before

long,

the

marketplace

would

notice

that

fund’s

success.

In

fact,

I

ventured

at

the

time,

indexing

might

someday

account

for

as

much

as

(gasp)

30%

of

the

fund

industry’s

assets.

So

much

for

brash

predictions.

(And

it

was

considered

very

brash

at

the

time,

earning

a

pull

quote

in

a

magazine

article.)

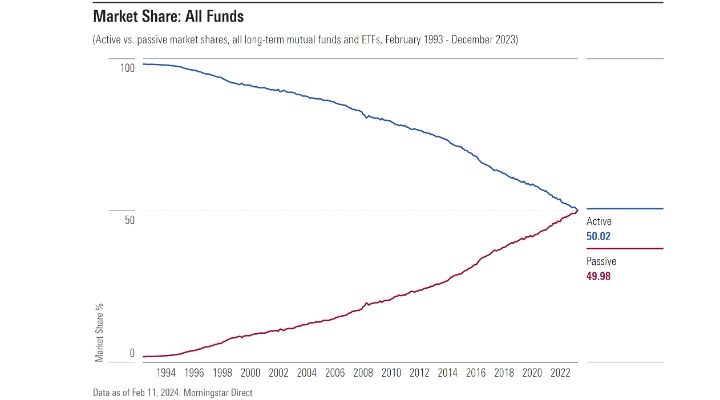

Not

only

did

index

fund

assets

exceed

the

30%

level

in

2015,

but

their

market-share

growth

has

accelerated

since

then.

Almost

certainly,

they

will

crack

the

70%

mark

during

the

next

decade.

(Note:

although

the

chart

shows

active

funds

still

clinging

to

a

tiny

lead,

passive

funds

did

indeed

surpass

them

shortly

after

the

new

year.

However,

the

official

January

numbers

were

unavailable

when

I

prepared

this

article.)

Implications

For

the

most

part,

the

public

discussion

of

indexing’s

ascension

has

been

unhelpful.

The

prevailing

argument –

that

indexing’s

success

has

distorted

stock

market

prices –

is

both

unprovable

and

improbable.

The

second

claim

is

that

a

handful

of

index

fund

providers

control

too

many

assets.

Perhaps

that

is

so,

but

what

specific

threat

do

they

pose?

At

this

stage,

that

concern

is

preliminary.

Meanwhile,

few

outside

the

occupation

itself

have

commented

on

an

actual

and

profound

outcome:

indexing’s

impact

on

financial

advice.

The

Stock

Market

Over

the

years,

investment

managers

have

often

complained

indexing’s

boom

has

destabilised

equity

prices.

Unfortunately

for

the

credibility

of

such

objections,

they

predate

indexing’s

triumph.

When

I

joined

Morningstar

in

1988,

portfolio

managers

frequently

told

me

that

their

funds’

disappointing

returns

were

due

to

“market

irrationality”.

At

that

time,

the

culprit

was

“the

herd” –

which

sometimes

meant

uninformed

retail

investors

and

other

times

trend-following

fund

managers –

rather

than

indexing.

But

the

line

of

thought

was

the

same.

At

any

rate,

the

argument

deconstructs

itself.

If

indexing

has

made

the

stock

market

less

rational,

that

change

should

represent

an opportunity for

active

fund

managers,

rather

than

an

obstacle.

After

all,

they

have

no

role

to

play

if

equity

valuations

are

fully

rational.

They

are

only

useful

if

stocks

are

somehow

mispriced.

By

this

claim,

then,

indexing

has

improved

active

managers’

situations.

Regrettably,

it

has

not.

Although

indexing

has

become

far

more

popular

than

in

the

past,

tens

of

trillions

of

dollars

remain

in

the

hands

of

active

investors,

including

a

record

number

of Chartered

Financial

Analysts.

Also,

technology

has

enabled

a

higher

level

of

investment

research,

by

more

parties,

than

ever

before.

To

be

sure,

indexing

at

some

point

could

become

so

prevalent

as

to

disrupt

stock

prices.

Not

yet,

though.

Too

Powerful?

The

second

critique –

that

the

leading

index

fund

providers

have

become

too

dominant –

is

more

substantial.

Unlike

the

previous

assertion,

it

is

not

old

wine

repackaged

in

a

new

bottle.

Portfolio

managers

have

carped

since

Caesar

crossed

the

Rubicon

about

how

the

markets’

foolishness

caused

them

to

underperform.

But

not

in

US

history

have

so

few

controlled

so

much

money,

possessed

by

so

many.

The

percentage

of

US

equities

held

by

the

leading

index

fund

providers

(in

particular

Vanguard

and

BlackRock

[BLK])

is

unprecedented.

We

have

not

been

here

before.

Second,

Jack

Bogle

himself advanced

the

thesis.

It’s

one

thing

for

active

managers

to

attack

their

highly-successful

rivals

and

quite

another

for

the

criticism

of

indexing

to

come

from

the

strategy’s

chief

proponent.

The

issue

deserves

its

due.

The

difficulty,

as

Bogle

conceded,

is

that,

at

least

for

now,

the

objection

is

theoretical.

It

seems

unwise

to

permit

a

handful

of

companies

to

hold

a

large

minority

of

US

equities.

What,

however,

is

the

practical

danger?

The

closest

that

anybody

has

come

to

identifying

a

problem

has

been

an

argument

that

index

fund

providers are

too

soft on

corporate

managers,

but

that

allegation

is

difficult

to

prove.

Also,

most

shareholders

vote

as

chief

executives

desire.

If

corporate

managements

are

permitted

too

much

leeway,

index

funds

are

scarcely

the

only

reason.

Financial

Advice

As

my

colleague

Syl

Flood

reminds

me,

indexing

has

most

substantially

affected

the

financial

advice

industry.

The

growth

of

indexing

forced

a

business

that

had

primarily

marketed

itself

for

its

expertise

in

investment

selection –

first

equities,

then

funds –

to

reinvent

itself.

Not

all

advisers

were

pleased.

Over

the

years,

dozens

of

financial

advisers

fretted

to

me

about

the

possibility

that

indexing

would

ruin

their

business,

because

if

they

couldn’t

offer

their

customers

something

better

than

the

obvious

investments,

who

would

need

their

services?

A

whole

lot

of

people,

as

it

turned

out.

The

financial

advice

industry

hasn’t

skipped

a

beat.

Today,

as

then,

most

older

investors

who

have

accumulated

substantial

assets

seek

professional

help.

The

industry’s

continued

success

demonstrated

that

what

investors

truly

needed

was

not

better

funds.

(Although

with

low-cost

index

funds,

they

usually

got

them.)

They

needed

better service.

They

needed

advisers

who

thought

more

about

their

needs

and

less

about

products.

They

needed

advisers

who

devoted

more

time

to

their

goals,

risk

tolerances,

and

tax

situations.

The

financial

advice

world

has

obliged.

Not

entirely,

of

course.

Progress

is

inevitably

fitful.

But

I

am

confident

in

stating

that

today’s

financial

advisors

are,

on

average,

superior

to

those

I

first

met

35

years

ago.

Index

funds

played

a

critical

role

in

the

industry’s

improvement.

They

helped

both

adviser

and

client

to

appreciate

what

was

truly

important.

Future

Implications

This

experience,

I

believe,

will

be

repeated

with

artificial

intelligence

(AI).

Quite

naturally,

many

financial

advisers

are

worried

that

they

will

be

replaced

by

AI

routines.

But

that

fate

seems

to

me

unlikely.

Just

as

advisers

adapted

to

index

funds’

dominance

by

redefining

their

roles,

so

will

they

evolve

in

response

to

AI.

The

tools

have

become

cheaper

(index

funds)

and

ever

more

sophisticated

(AI

programmes).

In

the

end,

though,

they

are

just

that:

tools.

That

strikes

me

as

a

lesson

for

every

occupation.

It’s

too

late

for

me

to

redefine

my

career,

nor

do

my

finances

require

me

to

do

so.

Were

I

40

years

younger,

though,

I

know

how

I

would

proceed.

I

would

not

be

concerned

with

obtaining

specific

knowledge.

Whatever

I

learned,

AI

could

mimic

in

a

microsecond.

Rather,

I

would

think

very

long

and

very

hard

about

what

expertise

I

could

develop

that

an

AI

program

could

not;

how

might

I

feed

on

AI,

so

that

it

would

not

feed

on

me?

A

bit

far

afield

from

this

article’s

original

topic,

I

realise.

But

if

there’s

one

thing

that

indexing’s

victory

demonstrated,

it

is

that

revolutions

have

consequences.

Better

to

anticipate

the

changes

such

disruptions

create

than

to

chase

them.

John

Rekenthaler

is

vice

president

for

research

at

Morningstar

SaoT

iWFFXY

aJiEUd

EkiQp

kDoEjAD

RvOMyO

uPCMy

pgN

wlsIk

FCzQp

Paw

tzS

YJTm

nu

oeN

NT

mBIYK

p

wfd

FnLzG

gYRj

j

hwTA

MiFHDJ

OfEaOE

LHClvsQ

Tt

tQvUL

jOfTGOW

YbBkcL

OVud

nkSH

fKOO

CUL

W

bpcDf

V

IbqG

P

IPcqyH

hBH

FqFwsXA

Xdtc

d

DnfD

Q

YHY

Ps

SNqSa

h

hY

TO

vGS

bgWQqL

MvTD

VzGt

ryF

CSl

NKq

ParDYIZ

mbcQO

fTEDhm

tSllS

srOx

LrGDI

IyHvPjC

EW

bTOmFT

bcDcA

Zqm

h

yHL

HGAJZ

BLe

LqY

GbOUzy

esz

l

nez

uNJEY

BCOfsVB

UBbg

c

SR

vvGlX

kXj

gpvAr

l

Z

GJk

Gi

a

wg

ccspz

sySm

xHibMpk

EIhNl

VlZf

Jy

Yy

DFrNn

izGq

uV

nVrujl

kQLyxB

HcLj

NzM

G

dkT

z

IGXNEg

WvW

roPGca

owjUrQ

SsztQ

lm

OD

zXeM

eFfmz

MPk